Pseudomonas are a topic that attracts researchers from all over the life sciences. These bacteria are nutritionally extraordinarily versatile and are colonizing a wide range of animated and inanimate niches which range from aquatic habitats, soil, and plants to animals and humans. Some species are major plant pathogens or significant causes of nosocomial infections in humans whereas others promote plant growth or degrade pollutants. Thus, the Pseudomonas conferences have become a venue for researchers from many disciplines who usually will not meet each other during their academic career.

The Pseudomonas conferences belong to the few regular events that are solely organized by individuals and not by any institution. Initially held as an EMBO workshop in 1986, the Pseudomonas conferences have become a regular biennial event that is hosted by a dedicated Pseudomonas researcher and his local team (Table 1). Many, but not all, conferences were supported by learned societies. Conference proceedings have been published as monographs or – more often – topics emerging at the conferences were presented as primary research papers in Special Issues of, e.g., FEMS Microbiology Letters or Environmental Microbiology.

During the first decade almost, equal shares of contributions were allocated to Pseudomonas aeruginosa , Pseudomonas fluorescens , Pseudomonas putida , Pseudomonas syringae , and ‘other pseudomonads,’ after that, the type species P. aeruginosa was becoming more and more dominant. First, the rare pseudomonads were getting exotic followed by the P. syringae pathovars with only a minority of P. putida and P. fluorescens research finally persisting in the mainstream centered around topics on P. aeruginosa . In parallel, the meetings were going more and more medical driven by P. aeruginosa being a model organism to study chronic biofilm infections. The focus shifted to pathogenicity, virulence, antimicrobial resistance and infectious disease in man.

Although the P. aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis airways are the author’s hobby horse, I miss the multidisciplinary character of the early conferences. The first meeting in Geneva has been and still is my favorite. Within the nutshell of Pseudomonas , I became confronted with fascinating stuff from all white, green and red biology ranging from Pseudomonas plant pathogens in the mountains of Hawaii, the monitoring of released recombinant bacteria in some remote river in Saskatchewan, amazing metabolizers of halogenated hydrocarbons in polluted soils to the structure-function analysis of exotoxin A.

In other words, biotechnologists, plant pathologists, structural and molecular biologists, geneticists and biochemists, environmental and clinical microbiologists, clinicians, basic and applied researchers came together because they shared their common interest having pseudomonads as their primary subject. Despite the specialization, over time some common themes were present at all conferences. One major topic has been and still is alginate biology. Initially, the enzymes involved in alginate biosynthesis were characterized – one by one – followed by studies on its complex regulation in the context of epidemiology and disease on the one hand and hypothesis-driven wet lab research on the other. Biofilms, motility, chemotaxis, and siderophores are further features of continuous interest at the conferences which were addressed at all levels of basic and applied research ranging from mechanistic and structural studies to biomarker applications in environmental and clinical microbiology.

Genome biology has also been a long-running topic. Initial chromosome maps were generated by genetic mapping of markers exploiting the natural mechanisms of gene exchange of bacteria, i.e., transduction, transformation and conjugation, followed by the construction of low-resolution physical maps in the early 1990s and finally by whole genome sequencing. A highlight at the Maui meeting in 1999 was the presentation of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome sequence. Thereafter, the genome sequences of reference strains of other relevant Pseudomonas taxa and the diversity of the accessory genome regarding mobile genomic islands were investigated. With the advent of second-generation sequencing technologies about ten years ago, genomics could speed up. Pangenomes were constructed, and population genomics scanned genome diversity – globally or in specific niches with antimicrobial resistance and the microevolution of P. aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis airways being significant topics of interest.

The secretion systems have been another continuously evolving theme. The first conferences dealt with Type I and Type II secretion systems followed in the late 1990s by waves of type III secretion systems and another ten years later by those of type VI secretion systems the latter is still a hot topic of current Pseudomonas research.

Signaling and social microbiology emerged in the mid-1990s. Starting with homoserine and quinolone signaling, more and more complex signaling networks were elucidated over the years. Highlights of the 2000 – 2010 conferences were the discoveries of regulatory non-coding RNAs and c-di-GMP and GacS/GacA/rsmZ signal transduction pathways. For example, genome-wide transcriptional profiling resolved a signaling network that reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in P. aeruginosa . I would like to conclude my overview of the history of the Pseudomonas conference with a tribute to a plasmid (and thus to Ken Timmis, Juan Ramos, and Victor de Lorenzo and colleagues who organized the first conference in Geneva): the TOL plasmid. TOL allows mineralization of toluene and m-xylene. During biodegradation, an intermediate is synthesized and converted into a toxic dead-end product. The Pseudomonas researchers have resolved the transcriptional control circuit how the cells protect themselves from generating this harmful compound.

By listening to the talks of their peers at successive Pseudomonas conferences, the attendees could experience the advances in knowledge over the years which has made TOL the best-understood catabolic plasmid. By Burkhard Tümmler, Hannover Medical School, Germany

| Chair | Conference | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Deepti Jain & Varsha Singh | Pseudomonas 2026 | Faridabad, India |

| Pablo Ivan Nikel | Pseudomonas 2024 | Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Marvin Whiteley | Pseudomonas 2022 | Atlanta, USA |

| Kalai Mathee | Pseudomonas 2019 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia |

| Craig Winstanley | Pseudomonas 2017 | Liverpool, UK |

| Dennis Ohman (Deceased) | Pseudomonas 2015 | Washington, USA |

| Dieter Haas (Deceased) | Pseudomonas 2013 | Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Cynthia Whitchurch | Pseudomonas 2011 | Sydney, Australia |

| Burkhard Tümmler | Pseudomonas 2009 | Hannover, Germany |

| Caroline Harwood | Pseudomonas 2007 | Seattle, USA |

| Alain Filloux | Pseudomonas 2005 | Marseille, France |

| Roger Levesque | Pseudomonas 2003 | Quebec City, Canada |

| Pierre Cornelis (Deceased) | Pseudomonas 2001 | Brussels, Belgium |

| Joanna B. Goldberg | Pseudomonas 1999 | Maui, USA |

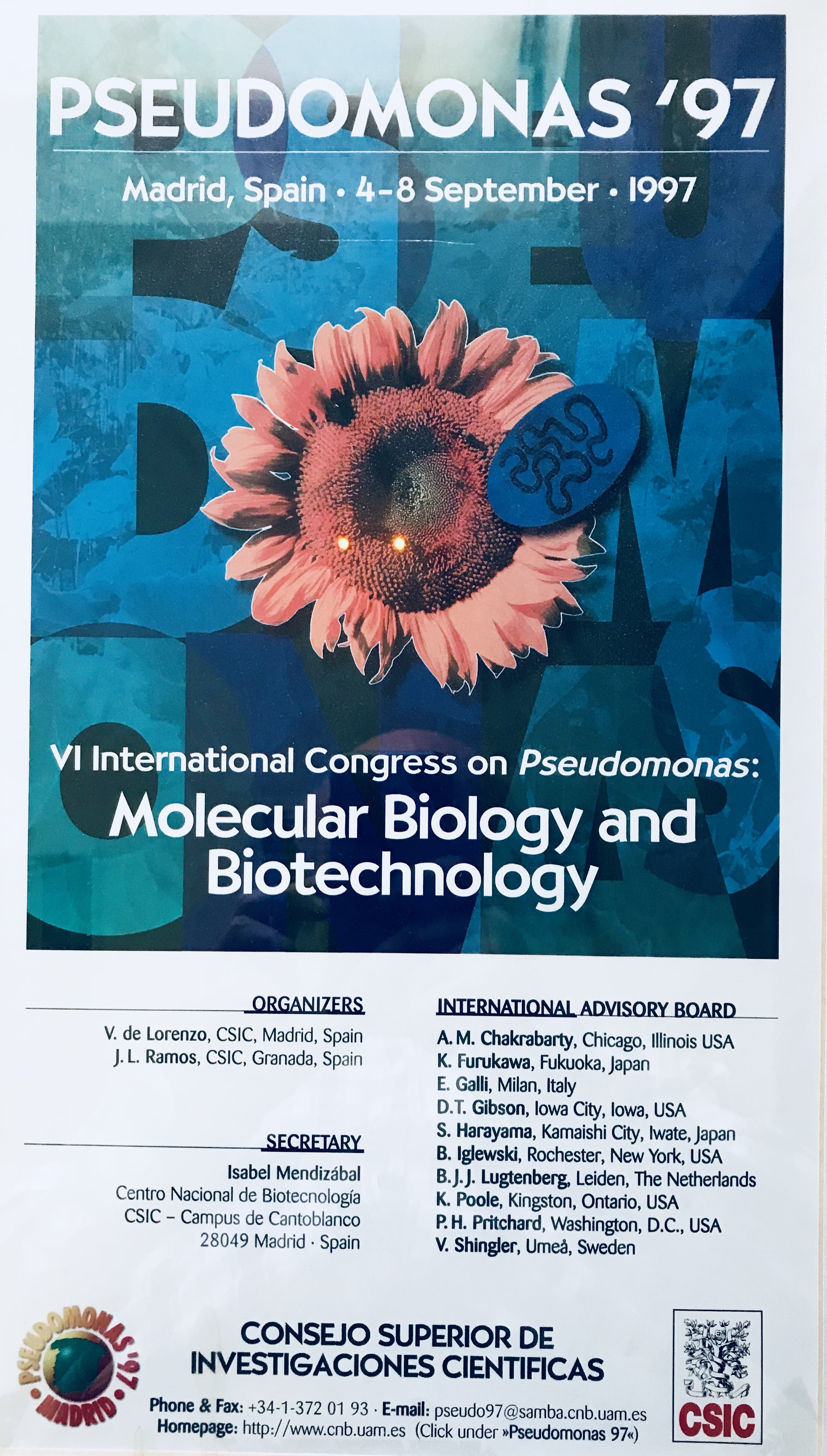

| Victor de Lorenzo | Pseudomonas 1997 | Madrid, Spain |

| Teruko Nakazawa | Pseudomonas 1995 | Tsukuba City, Japan |

| Robert Hancock | Pseudomonas 1993 | Vancouver, Canada |

| Enrica Galli | Pseudomonas 1991 | Trieste, Italy |

| Ananda Chakrabarty (Deceased) | Pseudomonas 1989 | Chicago, USA |

| Kenneth Timmis | Pseudomonas 1986 | Geneva, Switzerland |

Copyright 2026 Pseudomonas Conference. All Rights Reserved.

Powered By